Should You Start Your Legal Career at a Big Firm?

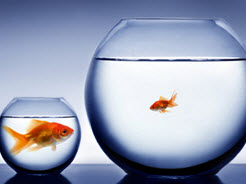

John Balestriere, writing in Above the Law, argues that young attorneys should not feel bound to follow the standard advice to start one’s career at a large firm to get “training.” As someone who spent 12 years at large firms and the last (almost) seven running my own small one, I’m in a position to weigh in on this topic. Although in my current position, I often expound on the benefits of small law firms, both for clients looking at what type of firm to engage and for experienced attorneys looking for a better way to practice law, I would still advise young attorneys looking to end up in the private sector to spend some time in a large firm.

First, an important caveat. Balestriere is a litigator, and my understanding (not based on experience) is that in that area, small firms and governmental agencies kind of throw young attorneys into handling trial work pretty much right away, as opposed to the large firm experience of having junior associates handle more behind-the-scenes work. I can’t speak to that; my advice in this post applies to those thinking of becoming a transactional attorney.

First, an important caveat. Balestriere is a litigator, and my understanding (not based on experience) is that in that area, small firms and governmental agencies kind of throw young attorneys into handling trial work pretty much right away, as opposed to the large firm experience of having junior associates handle more behind-the-scenes work. I can’t speak to that; my advice in this post applies to those thinking of becoming a transactional attorney.

Most of my early formative years were spent at Willkie Farr & Gallagher, a well-regarded “white shoe” firm in New York. Although I can’t say that all of my time there was used productively (I recall with non-fondness being asked by a quirky corporate partner to not leave my apartment on a Saturday and to wait for a call, which never came), I learned a huge amount, making me the lawyer I am today. My experience at Willkie, which I think is true of most big firms, had the following attributes that, I think, make the large firm experience worthwhile for junior attorneys:

- Plenty of potential mentors – I took assignments at Willkie from dozens of partners and senior associates, allowing me to gain a variety of experiences. If you’re working at a small firm, your boss may be a good mentor, but you’re not getting the benefit of seeing how many different lawyers do their job.

- High standards – I certainly don’t want to denigrate the many talented attorneys who work at small firms and for the government, and there are some real duds at big firms, but I was impressed with the intelligence and work ethic of the great majority of those I encountered at Willkie. They helped create expectations for my work that I still seek to meet.

- Network building – By working with a lot of attorneys at a large firm (or, as in my case, at a few big firms over several years), you will encounter and hopefully impress people who may be, later in your career, potential referral sources for business or otherwise in a position to help you. Two of my most important current clients are (1) a public company whose CEO was once my boss when I was an associate, and (2) a promising startup whose founder was an associate with me at Willkie.

Should You Start Your Legal Career at a Big Firm? Read More »

Personal Service – Many of my clients are referred from colleagues of mine, and the client doesn’t comparison shop with other firms before hiring me, but in situations where I find myself in a competition with another firm, that firm is often a mid-sized or large firm, rather than one with my profile. In that scenario, the appropriate strategy is to play up the differences between my way of doing business versus the large firm way. Accordingly, I emphasize the personal service that I provide. In a big firm (and I speak from much experience there), the pitch meeting will often be led by the senior partner, but after the deal starts, you find yourself dealing mostly with someone more junior. In contrast, I point out to the potential client that I am the sole point of contact, though I have experienced attorneys doing behind-the-scenes work to help me keep up with my workload and be able to be responsive to the requests of multiple clients.

Personal Service – Many of my clients are referred from colleagues of mine, and the client doesn’t comparison shop with other firms before hiring me, but in situations where I find myself in a competition with another firm, that firm is often a mid-sized or large firm, rather than one with my profile. In that scenario, the appropriate strategy is to play up the differences between my way of doing business versus the large firm way. Accordingly, I emphasize the personal service that I provide. In a big firm (and I speak from much experience there), the pitch meeting will often be led by the senior partner, but after the deal starts, you find yourself dealing mostly with someone more junior. In contrast, I point out to the potential client that I am the sole point of contact, though I have experienced attorneys doing behind-the-scenes work to help me keep up with my workload and be able to be responsive to the requests of multiple clients.

It has long been a common career path for corporate and securities attorneys to move to in-house legal positions after some training at a large firm. Many of those who do so eventually make another transition within their corporate employer: from attorney to non-attorney, assuming some sort of business role within the company. These ex-lawyers often justify the move by saying that the

It has long been a common career path for corporate and securities attorneys to move to in-house legal positions after some training at a large firm. Many of those who do so eventually make another transition within their corporate employer: from attorney to non-attorney, assuming some sort of business role within the company. These ex-lawyers often justify the move by saying that the