Before the SEC issued final rules recently relating to Title III crowdfunding – offerings of up to $1 million to accredited or non-accredited investors – there was much skepticism among the investment community whether these offerings could be completed in a cost effective manner, given the combination of a low offering limit and significant compliance requirements. The SEC addressed the concern in part by lifting the requirement that offerings over $500,000 be accompanied by audited financial statements, permitting reviewed statements in an issuer’s first crowdfunded offering. Another significant cost associated with these offerings is also how I make my living: legal disclosure requirements.

For comparison purposes, I think it would be useful to consider the requirements associated with the most common way to offer securities today in an exempt offering to non-accredited investors: a Rule 506(b) private placement. These offerings require the preparation of a disclosure document, the private placement memorandum (PPM), containing essentially the information required in a prospectus for a public offering. In other words, a lot of information, basically anything that the SEC has ever thought of requiring. Accordingly, a PPM is expensive to prepare.

For comparison purposes, I think it would be useful to consider the requirements associated with the most common way to offer securities today in an exempt offering to non-accredited investors: a Rule 506(b) private placement. These offerings require the preparation of a disclosure document, the private placement memorandum (PPM), containing essentially the information required in a prospectus for a public offering. In other words, a lot of information, basically anything that the SEC has ever thought of requiring. Accordingly, a PPM is expensive to prepare.

For Title III crowdfunded offerings, the equivalent of the PPM will be a Form C. Although the form will be required to be filed electronically via EDGAR, which has its own associated costs, the form itself requires somewhat less information than a PPM. To take an example, Form C requires the disclosure of holders of 20% of the issuer’s stock, as opposed to the 5% threshold that would be used in a registered offering document and a PPM. Time will tell what becomes common practice for preparation of the Form C offering document, and they may contain more disclosure than is strictly required, but based on an initial read of the rules, it will be a simpler (and therefore cheaper to produce) document.

However, unlike issuers that rely on Regulation D, issuers who complete a crowdfunded offering will have an ongoing annual disclosure requirement, essentially an annual Form C with all of the same information, except for offering-related disclosure. This requirement, while significant, is far less onerous than the requirements imposed on public companies (quarterly and periodic filings, proxy statements, etc.).

It is difficult to predict whether issuers will find this process to be cost effective, and we will all find out through experience. One factor that may tip the balance in favor of crowdfunding, even with the compliance costs, is that investors will not likely require the onerous terms that sophisticated institutional investors impose on issuers in private offerings – liquidation preferences, anti-dilution provisions, etc.

Rule 506(c), the provision arising out of the JOBS Act that enables companies to raise capital using general solicitation and advertising while still being exempt from SEC registration requirements, has always had the potential to revolutionize the capital raising process. With the ability of companies to connect easily with potential investors anywhere via the internet and social media, one could imagine a world where this supplants private placements under Rule 506(b), in which the investor base is, by definition, limited based on existing relationships with the company or its broker-dealer. While the use of Rule 506(c) has grown since enactment, it has nowhere near the usage rate of Rule 506(b). In 2017, Rule 506(c) offerings represented only 4% in dollar amount of all Regulation D offerings.

Rule 506(c), the provision arising out of the JOBS Act that enables companies to raise capital using general solicitation and advertising while still being exempt from SEC registration requirements, has always had the potential to revolutionize the capital raising process. With the ability of companies to connect easily with potential investors anywhere via the internet and social media, one could imagine a world where this supplants private placements under Rule 506(b), in which the investor base is, by definition, limited based on existing relationships with the company or its broker-dealer. While the use of Rule 506(c) has grown since enactment, it has nowhere near the usage rate of Rule 506(b). In 2017, Rule 506(c) offerings represented only 4% in dollar amount of all Regulation D offerings. The SEC has greatly expanded the number of public companies that can take advantage of the “scaled disclosure” provisions of Regulation S-K.

The SEC has greatly expanded the number of public companies that can take advantage of the “scaled disclosure” provisions of Regulation S-K. A recent Wall Street Journal article highlighted how

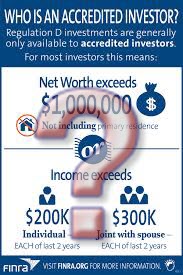

A recent Wall Street Journal article highlighted how  Securities offerings that are exempt from the SEC’s registration requirements often hinge on whether some or all of the investors are “

Securities offerings that are exempt from the SEC’s registration requirements often hinge on whether some or all of the investors are “ Carolyn Elefant, writing (sensibly) in Above the Law,

Carolyn Elefant, writing (sensibly) in Above the Law,  Gary Ross, another founder of a small corporate law firm, writes in Above the Law about

Gary Ross, another founder of a small corporate law firm, writes in Above the Law about  The SEC recently issued a long

The SEC recently issued a long