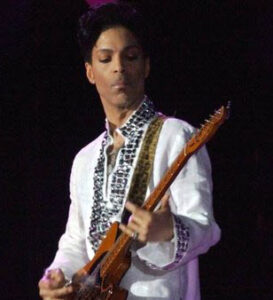

As part of the extensive media coverage of Prince’s recent death, it’s been reported that Prince died without a will as a result of his distrust of lawyers. If true, it’s a pretty disastrous result from an estate administration perspective. The problem is not so much that he has a large estate – under Minnesota’s laws of intestate succession, his siblings and half-siblings would receive their share of the assets. Rather, the issue is that the Prince business doesn’t end with his death. Sales of his music predictably skyrocketed post-mortem, and there are a number of decisions to be made with respect to music rights going forward, such as what to do with his extensive vault of unreleased music. Who makes those decisions? What if the heirs can’t agree on that?

The underlying problem, common among people who have come into sudden wealth, is an excessive distrust of professional advisors. There was some basis, in Prince’s case, for this belief, as he wasn’t the first talented young musician who wasn’t well-served in the negotiation of his early recording deals. And celebrities of all types are undoubtedly beset by family, friends and various hangers-on looking to get a piece of the pie. However, it’s easy to take this fear too far, to the point where you believe that any advice you’re getting is part of a scheme to separate you from your money. Taking this self-protective approach to the extreme of simply not listening to any professional advice is self-defeating.

The underlying problem, common among people who have come into sudden wealth, is an excessive distrust of professional advisors. There was some basis, in Prince’s case, for this belief, as he wasn’t the first talented young musician who wasn’t well-served in the negotiation of his early recording deals. And celebrities of all types are undoubtedly beset by family, friends and various hangers-on looking to get a piece of the pie. However, it’s easy to take this fear too far, to the point where you believe that any advice you’re getting is part of a scheme to separate you from your money. Taking this self-protective approach to the extreme of simply not listening to any professional advice is self-defeating.

So, what could someone like Prince do as a practical matter, if he’s being told that he absolutely has to get an estate plan in place, and he can’t bring himself to trust the estate planning attorney that was recommended to him? He fears (with some justification) that he’s in no position to be able to personally assess whether this attorney is a good one, and maybe he doesn’t fully trust whomever recommended the attorney. One approach is to borrow from medicine and get a second opinion from another attorney who isn’t close to the main one. The main attorney won’t necessarily love being vetted like that, but it can give the client comfort that everything is on the level. Obviously, this is a costly procedure that can only be afforded by wealthier clients, but it’s better to take out the insurance policy of getting a second opinion than lose sleep over whether you’re being fleeced.