I spent over five years of my career at Greenberg Traurig, LLP, a law firm of about 1,750 attorneys. Pretty big. Other large firms are content to maintain a smaller attorney count and grow only organically, not through lateral partner hires or mergers.

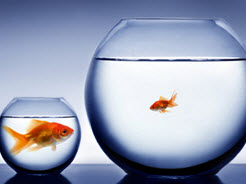

In my current incarnation as a one-member firm with some contract attorney help, it is somewhat academic to me whether a general practice firm should be 200 or 2,000 attorneys. More relevant to this boutique firm that limits itself to transactional law is whether it’s optimal to be a solo or to have, say, three or five partners, along with a couple of full-time associates and legal assistants. The right answer to this depends on the circumstances, and I’m not going to necessarily argue that my choice is the best, but I have some thoughts about points that are often made about this question.

In my current incarnation as a one-member firm with some contract attorney help, it is somewhat academic to me whether a general practice firm should be 200 or 2,000 attorneys. More relevant to this boutique firm that limits itself to transactional law is whether it’s optimal to be a solo or to have, say, three or five partners, along with a couple of full-time associates and legal assistants. The right answer to this depends on the circumstances, and I’m not going to necessarily argue that my choice is the best, but I have some thoughts about points that are often made about this question.

A major argument that is cited in favor of partnering up is that more attorneys mean greater economies of scale, i.e., you can more efficiently spread expenses among a larger group. However, the increasing flexibility of the economy, with outsourced and freelance work becoming more common, makes it possible for solos to purchase only the services they need. For example, I have an outside firm handle my bookkeeping and billing. The firm typically spends about three or four hours per month on my matters and is priced accordingly. If I had a few partners, there would be correspondingly more work, which would cost more money. Granted, once you reach a certain size, you’d be able to hire someone full-time, which could potentially mean some savings, but the key point here is that no one has to pay for more services than needed. If I started my firm 30 years ago, I probably would have had to hire an assistant to answer my phones, etc., and that person would have spent a lot of idle time being paid to wait around for work. There isn’t that sort of inefficiency in my business in 2014.

Another rationale in favor of having partners is as protection against a serious illness or injury derailing the firm. If I was out of commission for several months, my regular clients would need to seek help from another firm. If I had a few partners, they would be able to fill in for me in my absence. To some extent, I can protect myself (and I have) by purchasing long-term disability insurance to cover a portion of my income in the case of an extended absence. But the firm itself would likely need to take some time to recover its client base when I returned to work, since in all likelihood, some of my clients that turned to other firms in my absence would continue to use those firms. Accordingly, I think the risk of disruption due to attorney incapacity is the one clear flaw of the solo model.

Finally, there is the somewhat intangible quality of a multi-partner firm seeming more substantial and real than a solo firm and therefore a “safer” choice for some clients. Undoubtedly, a newly admitted attorney launching a solo practice would find it difficult to land clients that could be in a position to hire larger firms. However, in my case, I thought at the time I launched my firm that my background of having spent 12 years at large firms, including as a partner, would be reassuring to clients wondering if a solo attorney had the chops to handle sophisticated matters, and fortunately I’ve found that I’ve been able to attract clients that are used to engaging larger firms.